Okapi

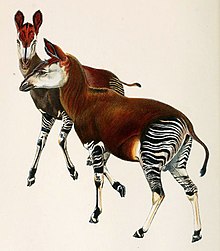

The okapi (/oʊˈkɑːpiː/; Okapia johnstoni), also known as the forest giraffe or zebra giraffe, is an artiodactyl mammal native to the northeast of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in Central Africa. Although the okapi bears striped markings reminiscent of zebras, it is most closely related to the giraffe. The okapi and the giraffe are the only living members of the family Giraffidae. The okapi stands about 1.5 m (4.9 ft) tall at the shoulder and has an average body length around 2.5 m (8.2 ft). Its weight ranges from 200 to 350 kg (440 to 770 lb). It has a long neck, and large, flexible ears. Its coat is a chocolate to reddish brown, much in contrast with the white horizontal stripes and rings on the legs and white ankles. Male okapis have short, hair-covered protuberances called ossicones, less than 15 cm (5.9 in) in length. Females possess hair whorls, and ossicones are absent.

Okapis are primarily diurnal, but may be active for a few hours in darkness. They are essentially solitary, coming together only to breed. Okapis are herbivores, feeding on tree leaves and buds, grasses, ferns, fruits, and fungi. Rut in males and estrus in females does not depend on the season. In captivity, estrous cycles recur every 15 days. The gestational period is around 440 to 450 days long, following which usually a single calf is born. The juveniles are kept in hiding, and nursing takes place infrequently. Juveniles start taking solid food from three months, and weaning takes place at six months.

Okapis inhabit canopy forests at altitudes of 500–1,500 m (1,600–4,900 ft). They are endemic to the tropical forests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where they occur across the central, northern, and eastern regions. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources classifies the okapi as endangered. Major threats include habitat loss due to logging and human settlement. Extensive hunting for bushmeat and skin and illegal mining have also led to a decline in populations. The Okapi Conservation Project was established in 1987 to protect okapi populations.

| Okapi | |

|---|---|

| |

| An okapi at Disney's Animal Kingdomin Florida | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Giraffidae |

| Genus: | Okapia Lankester, 1901 |

| Species: | O. johnstoni |

| Binomial name | |

| Okapia johnstoni (P.L. Sclater, 1901) | |

| |

| Range of the okapi | |

Okapis in Zoos

Around 100 okapis are in accredited Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) zoos, but not many zoos house these elusive creatures. The okapi population is managed by the AZA's Species Survival Plan, a breeding program that works to ensure genetic diversity in the captive population of endangered animals.

The San Diego Zoo has exhibited okapis since 1956, and had their first birth of an okapi in 1962. Since then, over 60 births have occurred between the zoo and the San Diego Zoo Safari Park, with the most recent being Mosi, a male calf born in early August 2017 at the San Diego Zoo. [2]

The Brookfield Zoo in Chicago has also greatly contributed to the captive population of okapis in accredited zoos. The zoo has had 28 okapi births since 1959. [3]

Other North American Zoos that exhibit and breed okapis include Bronx Zoo (New York); Denver Zoo, Cheyenne Mountain Zoo (Colorado); Houston Zoo, Dallas Zoo, San Antonio Zoo (Texas); Disney's Animal Kingdom, Miami Zoo, Tampa's Lowry Park Zoo, Jacksonville Zoo (Florida); Los Angeles Zoo(California); Saint Louis Zoo (Missouri); Cincinnati Zoo, Columbus Zoo (Ohio); Memphis Zoo(Tennessee); Maryland Zoo (Maryland); and Omaha's Henry Doorly Zoo (Nebraska).

In Europe, zoos that exhibit and breed okapis include Chester Zoo, London Zoo, Bristol Zoo, Marwell Zoo, The Wild Place (United Kingdom); Dublin Zoo (Ireland); Berlin Zoo, Frankfurt Zoo, Wilhelma Zoo, Wuppertal Zoo, Cologne Zoo, Leipzig Zoo (Germany) and Antwerp Zoo (Belgium); Zurich Zoo, Zoo basel (Switzerland); Copenhagen Zoo (Denmark); Rotterdam Zoo, Safaripark Beekse Bergen(Netherlands) and Dvůr Králové Zoo (Czech Republic), Wrocław Zoo (Poland); Bioparc Zoo de Doué, Zooparc de Beauval (France); Lisbon Zoo (Portugal).[4][5]

Etymology and taxonomy

Okapia johnstoni was first described as Equus johnstoni by English zoologist Philip Lutley Sclater in 1901.[7] The generic name Okapia derives from the Lese Karo name o'api, while the specific name(johnstoni) is in recognition of the British Governor of Uganda, Sir Harry Johnston, who first acquired an okapi specimen for science from the Ituri Forest while repatriating a group of Pygmies to the Belgian Congo.[8][9] The animal was brought to prominent European attention by speculation on its existence found in press reports covering Henry Morton Stanley's journeys in 1887. Remains of a carcass were later sent to London by the English adventurer and colonial administrator Harry Johnston and became a media event in 1901.[10]

In 1901, Sclater presented a painting of the okapi before the Zoological Society of London that depicted its physical features with some clarity. Much confusion arose regarding the taxonomical status of this newly discovered animal. Sir Harry Johnston himself called it a Helladotherium, or a relative of other extinct giraffids.[11] Based on the description of the okapi by Pygmies, who referred to it as a "horse", Sclater named the species Equus johnstoni.[12] Subsequently, Lankester declared that the okapi represented an unknown genus of the Giraffidae, which he placed in its own genus, Okapia, and assigned the name Okapia johnstoni to the species.[13]

In 1902, Swiss zoologist Charles Immanuel Forsyth Major suggested the inclusion of O. johnstoni in the extinct giraffid subfamily Palaeotraginae. However, the species was placed in its own subfamily Okapiinae, by Swedish palaeontologist Birger Bohlin in 1926,[14]mainly due to the lack of a cingulum, a major feature of the palaeotragids.[15] In 1986, Okapia was finally established as a sister genus of Giraffa on the basis of cladistic analysis. The two genera together with Palaeotragus constitute the tribe Giraffini.[16]

Evolution

The earliest members of the Giraffidae first appeared in the early Miocene in Africa, having diverged from the superficially deer-like climacoceratids. Giraffids spread into Europe and Asia by the middle Miocene in a first radiation. Another radiation began in the Pliocene, but was terminated by a decline in diversity in the Pleistocene.[17] Several important primitive giraffids existed more or less contemporaneously in the Miocene (23-10 million years ago), including Canthumeryx, Giraffokeryx, Palaeotragus, and Samotherium. According to palaeontologist and author Kathleen Hunt, Samotherium split into Okapia (18 million years ago) and Giraffa (12 million years ago).[18] However, J. D. Skinner argued that Canthumeryx gave rise to the okapi and giraffe through the latter three genera and that the okapi is the extant form of Palaeotragus.[19] The okapi is sometimes referred to as an example of a living fossil, as it has existed as a species over a long geological time period, and morphologically resembles more primitive forms (e.g. Samotherium).[13][20]

A 2016 study found that the common ancestor of giraffe and okapi lived about 11.5 million years ago.[21]

Characteristics

The okapi is a medium-sized giraffid, standing 1.5 m (4.9 ft) tall at the shoulder. Its average body length is about 2.5 m (8.2 ft) and its weight ranges from 200 to 350 kg (440 to 770 lb).[22] It has a long neck, and large and flexible ears. The coat is a chocolate to reddish brown, much in contrast with the white horizontal stripes and rings on the legs and white ankles. The striking stripes make it resemble a zebra.[23] These features serve as an effective camouflage amidst dense vegetation. The face, throat, and chest are greyish white. Interdigital glandsare present on all four feet, and are slightly larger on the front feet.[24] Male okapis have short, hair-covered horns called ossicones, less than 15 cm (5.9 in) in length. The okapi exhibits sexual dimorphism, with females 4.2 cm (1.7 in) taller on average, slightly redder, and lacking prominent ossicones, instead possessing hair whorls.[25][26]

The okapi shows several adaptations to its tropical habitat. The large number of rod cells in the retina facilitate night vision, and an efficient olfactory system is present. The large auditory bullae allow a strong sense of hearing. The dental formula of the okapi is 0.0.3.33.1.3.3.[24] Teeth are low-crowned and finely cusped, and efficiently cut tender foliage. The large caecum and colon help in microbial digestion, and a quick rate of food passage allows for lower cell wall digestion than in other ruminants.[27]

The okapi can be easily distinguished from its nearest extant relative, the giraffe. It is much smaller and shares more external similarities with the deer and bovids than with the giraffe. While both sexes possess horns in the giraffe, only males bear horns in the okapi. The okapi has large palatine sinuses, unique among the giraffids. Morphological similarities shared between the giraffe and the okapi include a similar gait – both use a pacing gait, stepping simultaneously with the front and the hind leg on the same side of the body, unlike other ungulates that walk by moving alternate legs on either side of the body[28] - and a long, black tongue (longer in the okapi) useful in plucking buds and leaves, as well as for grooming.[27]

Ecology and behaviour

Okapis are primarily diurnal, but may be active for a few hours in darkness.[29] They are essentially solitary, coming together only to breed. They have overlapping home ranges and typically occur at densities around 0.6 animals per square kilometre.[23] Male home ranges average 13 km2 (5.0 sq mi), while female home ranges average 3–5 km2 (1.2–1.9 sq mi). Males migrate continuously, while females are sedentary.[30] Males often mark territories and bushes with their urine, while females use common defecation sites. Grooming is a common practice, focused at the earlobes and the neck. Okapis often rub their necks against trees, leaving a brown exudate.[24]

The male is protective of his territory, but allows females to pass through the domain to forage. Males visit female home ranges at breeding time.[27] Although generally tranquil, the okapi can kick and butt with its head to show aggression. As the vocal cords are poorly developed, vocal communication is mainly restricted to three sounds — "chuff" (contact calls used by both sexes), "moan" (by females during courtship) and "bleat" (by infants under stress). Individuals may engage in Flehmen response, a visual expression in which the animal curls back its upper lips, displays the teeth, and inhales through the mouth for a few seconds. The leopard is the main predator of the okapi.[24]

Diet

Okapis are herbivores, feeding on tree leaves and buds, grasses, ferns, fruits, and fungi. They are unique in the Ituri forest as they are the only known mammal that feeds solely on understory vegetation, which they use their 18=in-long tongues to selectively groom with. They prefer to feed in treefall gaps. The okapi has been known to feed on over 100 species of plants, some of which are known to be poisonous to humans and other animals. Fecal analysis shows that none of those 100 species dominates the diet of the okapi.[citation needed] Staple foods comprise shrubs and lianas. The main constituents of the diet are woody, dicotyledonous species; monocotyledonous plants are not eaten regularly. In the Ituri forest, the okapi feeds mainly upon the plant families Acanthaceae, Ebenaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Flacourtiaceae, Loganiaceae, Rubiaceae, and Violaceae.[24][30]

Reproduction

Female okapis become sexually mature at about one-and-a-half years old, while males reach maturity after two years. Rut in males and estrus in females does not depend on the season. In captivity, estrous cycles recur every 15 days.[27][31] The male and the female begin courtship by circling, smelling and licking each other. The male shows his dominance by extending his neck, tossing his head, and protruding one leg forward. This is followed by mounting and copulation.[25]

The gestational period is around 440 to 450 days long, following which usually a single calf is born, weighing 14–30 kg (31–66 lb). The udder of the pregnant female starts swelling two months before parturition, and vulval discharges may occur. Parturition takes 3–4 hours, and the female stands throughout this period, though she may rest during brief intervals. The mother consumes the afterbirth and extensively grooms the infant. Her milk is very rich in proteins and low in fat.[27]

As in other ruminants, the infant can stand within 30 minutes of birth. Although generally similar to adults, newborn calves have false eyelashes, a long dorsal mane, and long white hairs in the stripes. These features gradually disappear and give way to the general appearance within a year. The juveniles are kept in hiding, and nursing takes place infrequently. Calves are known not to defecate for the first month or two of life, which is hypothesized to help avoid predator detection in their most vulnerable phase of life.[citation needed] The growth rate of calves is appreciably high in the first few months of birth, after which it gradually declines. Juveniles start taking solid food from three months, and weaning takes place at six months. Horn development in males takes one year after birth. The okapi's typical lifespan is 20 to 30 years.[24]

Habitat and distribution

Okapis inhabit canopy forests at altitudes of 500–1,500 m (1,600–4,900 ft). They are endemic to the tropical forests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. They do not occur in gallery forests, habitats disturbed by human settlement, and swamp forests, but may occasionally use seasonally inundated areas. In the wet season, they visit rocky inselbergs that offer forage uncommon elsewhere. The population density of the okapi averaged 0.53 animals per square kilometre in mixed Cynometera forests.[30]

The okapi occurs across central, northern, and eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, and north and east of the Congo River. The species ranges from the Maiko forest northward to the Ituri forest, then through the river basins of the Rubi, Lake Tele, and Ebola to the west and the Ubangi River further north. Smaller populations exist west and south of the Congo. They are also common in the Wambaand Epulu areas. The okapi is extinct in Uganda.[1]

Threats and conservation

The IUCN classifies the okapi as endangered.[32] It is fully protected under Congolese law. The Okapi Wildlife Reserve and Maiko National Park support significant populations of the okapi, though a steady decline in numbers has occurred due to several threats. Other areas of occurrence are the Rubi Tele Hunting Reserve and the Abumombanzi Reserve. Major threats include habitat loss due to loggingand human settlement. Extensive hunting for bushmeat and skin and illegal mining have also led to population declines. A threat that has emerged quite recently is the presence of illegal armed groups around protected areas, inhibiting conservation and monitoring actions. A small population occurs north of the Virunga National Park, but is bereft of protection due to the presence of armed groups in the vicinity.[1] In June 2012, a gang of poachers attacked the headquarters of the Okapi Wildlife Reserve, killing six guards and other staff[33]as well as all 14 okapis at their breeding center.[34]

The Okapi Conservation Project, established in 1987, works towards the conservation of the okapi, as well as the growth of the indigenous Mbuti people.[1] In November 2011, the White Oak Conservation center and Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens hosted an international meeting of the Okapi Species Survival Plan and the Okapi European Endangered Species Programme at Jacksonville, which was attended by representatives from zoos from the USA, Europe, and Japan. The aim was to discuss the management of captive okapis and arrange support for okapi conservation. Many zoos in North America and Europe currently have okapis in captivity.[35]

History

Although the okapi was unknown to the Western world until the 20th century, it may have been depicted since the early fifth century BCE on the façade of the Apadana at Persepolis, a gift from the Ethiopian procession to the Achaemenid kingdom.[36]

For years, Europeans in Africa had heard of an animal that they came to call the African unicorn. In his travelogue of exploring the Congo, Henry Morton Stanley mentioned a kind of donkey that the natives called the atti, which scholars later identified as the okapi. Explorers may have seen the fleeting view of the striped backside as the animal fled through the bushes, leading to speculation that the okapi was some sort of rainforest zebra.[citation needed]

When the British governor of Uganda, Sir Harry Johnston, discovered some pygmy inhabitants of the Congo being abducted by a showman for exhibition, he rescued them and promised to return them to their homes. The grateful pygmies fed Johnston's curiosity about the animal mentioned in Stanley's book. Johnston was puzzled by the okapi tracks the natives showed him; while he had expected to be on the trail of some sort of forest-dwelling horse, the tracks were of a cloven-hoofed beast.[37]

Though Johnston did not see an okapi himself, he did manage to obtain pieces of striped skin and eventually a skull. From this skull, the okapi was correctly classified as a relative of the giraffe; in 1901, the species was formally recognized as Okapia johnstoni.[8]